Cholesterol is vital to the function of our body. So how does something so essential turn into ‘plaque’?

First, let’s clarify something: cholesterol is not the same thing as LDL or HDL.

LDL and HDL are lipoproteins. Although our body needs cholesterol it’s not water soluble, so it can’t travel through the blood by itself. Something needs to carry it, and that something is a lipoprotein — as in low density lipoprotein (LDL) and high density lipoprotein (HDL).

LDL takes fresh cholesterol from the liver to the body and HDL takes it from the body back to the liver for possible excretion via the gut.

A transport analogy is often used to describe this arrangement where the lipoprotein is like a bus, car or boat that ferries cholesterol around. There are other passengers on board too, such as triglycerides and proteins.

Standard blood tests give us an idea of how much cholesterol is on a bus, and we assume that if there’s a fair bit on the LDL buses that’s bad, but if it’s on the HDL service it’s good.

What’s tricky about this is that in reality LDL isn’t all ‘bad’ and HDL isn’t all ‘good’. There are different types of both, some harmless and some not so harmless.

What might be helpful is knowing how many buses there are, because when there are too many, there’s a greater chance of an accident or a mishap in the arteries.

Before we get to what that looks like, let’s go back to the arteries.

They have a thin inner layer, and while that layer is only one cell thick, it’s important because it releases chemicals that control what happens in the arteries, e.g. opening and closing them, blood clotting and immune function.

One of those chemicals is nitric oxide, which is generally thought of as balancing our feel-good chemicals serotonin and dopamine, but here it opens the arteries to increase blood flow and lower blood pressure.

The trouble is the inner lining gets damaged by that list of stressors and the chemicals they release. For instance, a damaged artery produces less nitric oxide so blood flow is reduced. As a result blood pressure can increase.

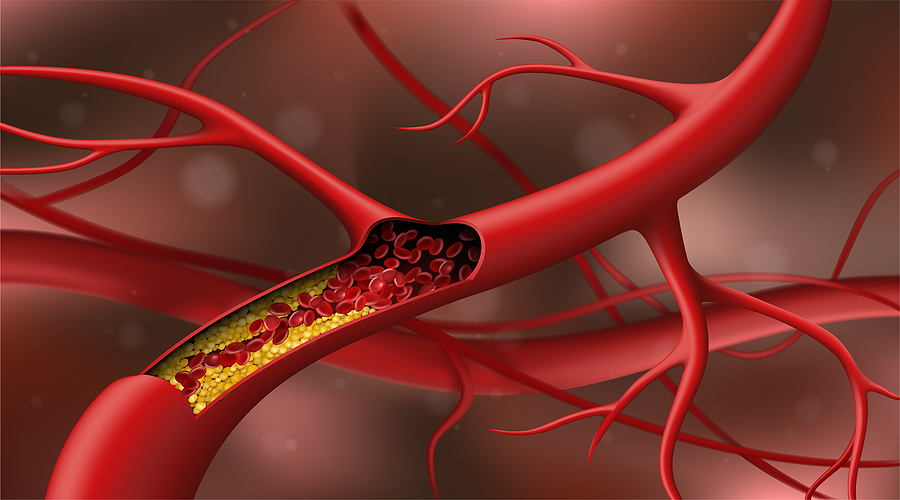

Damaged arteries are also at risk of a stray LDL particle (bus) breaking through the lining and lodging there. Certain types of LDL (e.g. smaller ones) are more likely to do this. The LDL also becomes damaged, other particles pile on and a sticky, fatty build-up occurs in the arterial wall.

This is plaque, and it can push into the open space of the artery, making it harder for blood to pass through.

Plaque is initially soft, but as our immune system and the artery sense that something’s wrong the body creates a fibrous cap over the top of the fatty build-up. Eventually, calcium can be laid down in this cap.

Calcification has an upside and a downside.

On the upside, calcified plaque is stable and isn’t going anywhere. The danger with softer plaque is that it might rupture, and if the cap comes loose it could cause a blockage. The body responds to a rupture by forming a blood clot to try to contain it, and clots and blockages in arteries aren’t good.

On the downside, calcification makes the artery stiffer. This is what’s referred to as ‘hardening of the arteries’.

Angela Maas says the plaque in women’s arteries is more likely to be mild and distributed more broadly than in men, but combined with arterial constriction and spasm it could contribute to reduced blood flow and oxygen deficiency.

Measuring calcification: coronary artery calcium (CAC) score

A CT scan is used to do this. Mostly it’s done to assess heart attack risk if, say, your cholesterol is creeping up and you have a family history of early heart disease.

If, in addition to those two, calcified plaque shows up on your scan, expect your GP to hand you a prescription for statins.

Scoring starts at zero, which indicates very low risk. If you have high cholesterol and a family history but zero plaque, your doctor will probably suggest ‘keeping an eye on things’ and having another scan in a few years.

A score of 1-10 or even 1-100 is still fairly low. Above that though there’s likely to be a conversation about medication. Above 400 your risk is on the high side.

On the face of it CAC might seem like the holy grail for predicting a heart attack, but it’s important to appreciate what it does and doesn’t mean if you have a positive score.

As we’ve seen, calcified plaque has pluses and minuses. The minus is you’ve got plaque in your arteries. The plus is it’s stable. You’re not getting the entire picture though because softer plaque doesn’t show up on a scan.

Over time calcification either increases or stays the same; it doesn’t go away. Statins help to stabilise it, which means more calcification. So if you had another scan after a being on statins you could expect your score to be higher.

Photo Source: Bigstock