This month the Australian Bureau of Statistics published data on causes of death for last year. While dementia is up there again, we’re making progress.

For the past few years, it’s been a close second to heart disease as the leading cause of death for Australians. It’s already the major cause of death for women.

Heart disease is slightly less of a threat than it was because we’ve become better at managing it. Having said that, about 20 Australian women die from heart disease each day, and doctors are still missing symptoms and under-treating women. So we need to stay vigilant.

The incidence of dementia is creeping up because the greatest risk factor is age. As we know, our population’s getting older, and women outlive men. And that’s a risk factor we can’t change.

These figures show how much things have shifted in the last 50 years:

- In 1974 around 34,600 Australian died from heart disease, and their median age was 72-73.

- In 2023 around 16,900 people died from heart disease, and their median age was 83-84. Half as many deaths, and at a later age.

- In 1974 only 338 dementia-related deaths were recorded. Median age 80-81.

- In 2023 dementia accounted for nearly 16,700 deaths, and the median age was 88-89. A big, big increase, though at a later age.

So where are we making progress?

Medicine has been slow to develop drugs that steady or stop the disease, much less reverse it, but more recently there’s been a glimmer on the horizon.

Two drugs — marketed as Leqembi and Kisunla — that have been approved for use in the US as well as China, Japan and Israel, reduce the amyloid plaques in the brain responsible for causing Alzheimer’s.

Both are given by infusion and have been shown to help slow the development of Alzheimer’s in its early stages, though they won’t help more advanced cases.

But there are possible side effects, including headaches, dizziness, and bleeds in the brain, and European regulators aren’t yet convinced that the benefits outweigh the risks.

In Australia, it was widely thought that the Therapeutic Goods Administration would approve the use of Leqembi, but this month they knocked it back, also citing concerns about risks vs benefits.

That’ll disappoint people, but there are now two companies going head-to-head to get their products accepted and that can only move things forward. Sometimes it takes a lot of small advances to manage a disease, and these drugs are considered a breakthrough.

The other way to address dementia is through prevention. While we can’t prevent ageing, researchers are making strides in understanding other risk factors and how to address them.

And, it seems, there’s no shortage of risk factors. In another post this month I’ve written about the work done in Scandinavia and being replicated in other countries.

Aside from that, much of what we know about prevention has come from a body called The Lancet Commission on Dementia.

The Lancet is a major (British) medical journal. In 2017 it convened scientists from around the world to review the best available evidence and make recommendations on how to prevent and manage dementia.

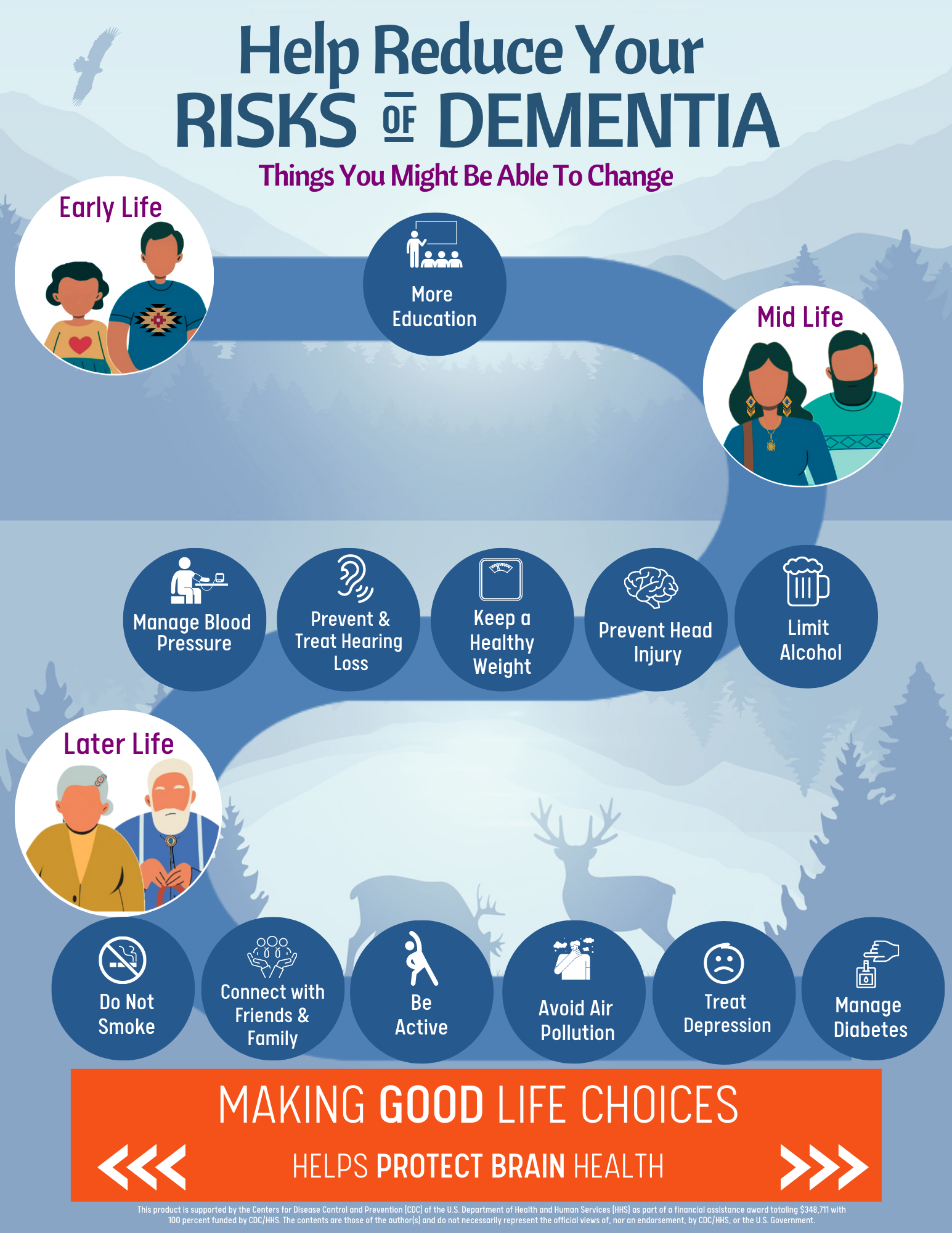

The Commission’s latest (2024) report identifies 14 risk factors and argues that evidence is stronger than ever that tackling these will reduce the likelihood of developing the disease.

Their 14 risk factors are: low levels of education in early life, hearing loss, high blood pressure, smoking, obesity, depression, physical inactivity, diabetes, excessive alcohol consumption, traumatic brain injury, air pollution, social isolation, untreated vision loss, and high LDL cholesterol.

The image I’ve used is one of the infographics developed in 2020 when the Commission had identified 12 risk factors. Vision loss and LDL cholesterol have been added since.

The focus of the Scandinavian trial and its numerous off-shoots is on diet, exercise, cognitive training, social activity, and cardiovascular health. So there’s a lot of investigation taking place into several risk factors.

In addition, the Lancet Commission has highlighted issues such as hearing and vision loss that contribute to social isolation

All of which is good news. We already have far more information on prevention than any previous generation of women has had. Our job is to pick it up and use it.

Image source: International Association for Indigenous Aging